What is steel, anyway?

Wikipedia tells us that steel is an iron-based alloy with a carbon content of between 0.02% and 2% by mass, which may or may not contain other chemical elements (impurities).

The elements added to iron modify its physico-chemical characteristics.

- Carbon is always present, but in variable quantities, which influences the alloy’s maximum hardness or its ability to be enamelled, for example. When the carbon content exceeds 2.1%, we speak of cast iron.

- chromium is added to produce stainless steel (or inox).

- other elements (cobalt, manganese, nickel, etc.) are added to modify hardenability and the effectiveness of heat treatments, for example.

Which steel for which use?

There is a wide variety of steels, from the most classic to the most advanced industrial, not forgetting artisanal blast furnace steel, still produced by a few experts. For my part, I’ll just mention the sheet steel references, for stock removal (the act of removing material from an already-formed part). I have neither the know-how nor the equipment of a blacksmith. Here are a few suggestions on how to get started, and even produce quality objects. You can create a beautiful tool from modest steel, but there are many other parameters.

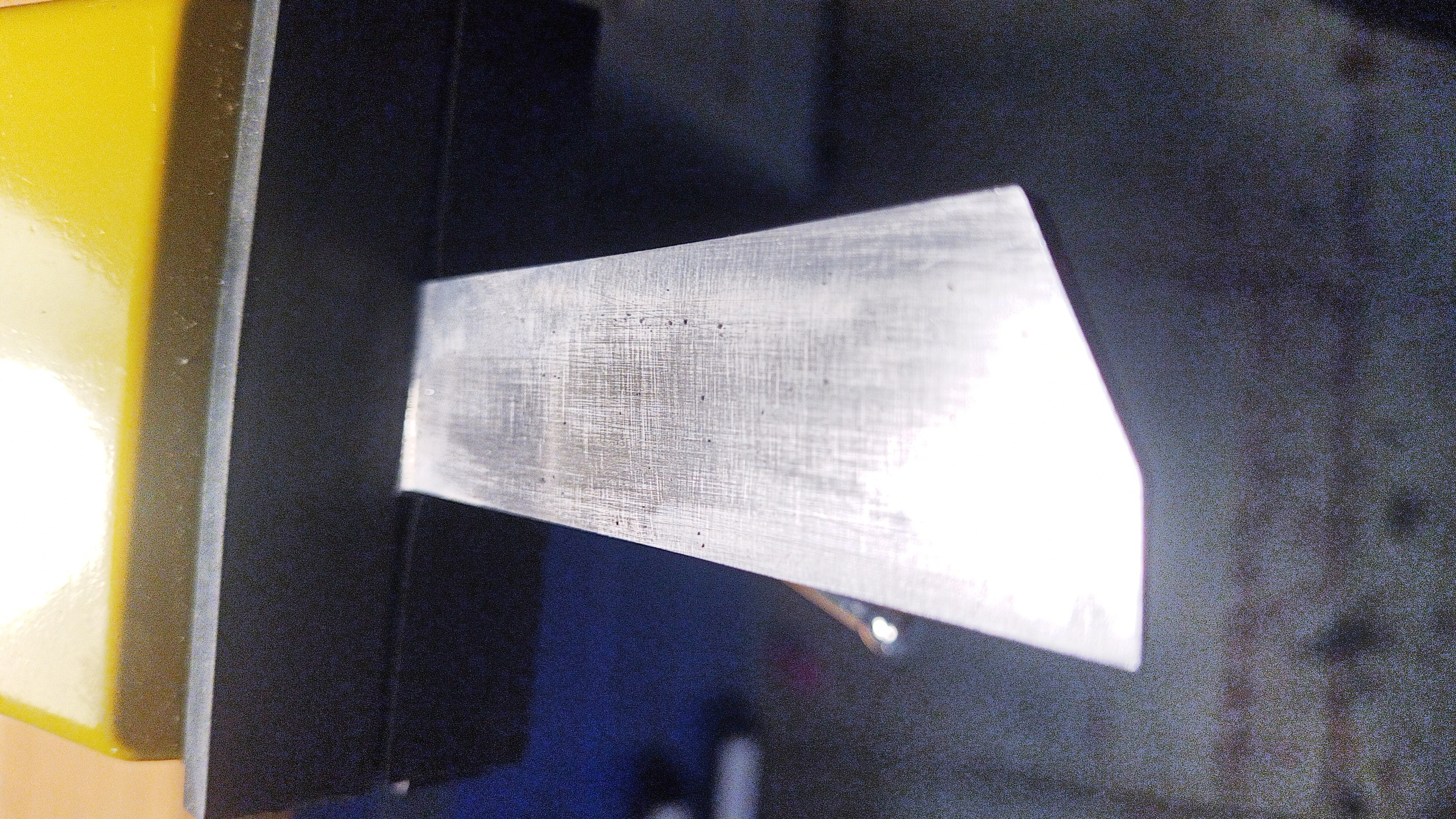

For blades

- a steel with a high carbon content, suitable for hard, very sharp blades: XC75 (1075) if you’re on a budget, or the even harder XC100 (1095) produced in Europe.

- a common, inexpensive stainless steel such as Z40 (X46Cr13)

- a higher-quality stainless steel such as 14C28N, made in Sweden by Alleima (formerly Sandvik)

For folding-knife springs

Take Z20 (X20Cr13), for example, which remains softer than Z40 after hardening.

For folding-knife plates

X6Cr17 (1.4016 or 430) is a good choice. It is a ferritic stainless steel, and therefore not hardenable. Note that this is not a problem except for liner-lock folding knives, which require reinforced plates.

Please note

- this list is by no means exhaustive!

- if you don’t have a tempering furnace, forget stainless steel. It has to be heated to around 1050°C for 5 to 10 minutes, away from oxygen, which is too restrictive for DIY.

- carbon steel changes appearance over time, which is normal. Always wash and dry these blades by hand without delay. And don’t leave them stuck in a lemon or an apple!

Where does it come from?

When you buy steel, you should ask yourself where it is produced, under what conditions, and how far it travels from factory to workshop. Given the price differences, it’s often possible to find European steel (for europeans!), which nevertheless offers a few guarantees.

Where to find steel?

When you want to make your first knife, and you’re looking for information on the web, you’ll find all kinds of more or less useful advice. They vary according to “who’s talking”: the professional, the survivalist, the person who can afford specialized machinery or, on the contrary, the do-it-yourselfer. When it comes to steel, for example, there are several schools of thought:

- salvage specialists who use an old file to make a pocketknife;

- the “extreme blacksmiths”, who start with a rusty car part;

- the “reasonable”, who generally use a steel bar with a real traceability (for blacksmiths) or a sheet of known origin (for stock removal). It all depends on the experience you’re looking for. If it’s the pleasure of transforming one object into another with the means at hand, all approaches are valid. On the other hand, you don’t have to be a stickler for the quality of the result, and you need to have a certain resistance to frustration.

If, on the other hand, you’re hoping to get a quality knife, I’d advise you to give it your best shot.

Why is it more reliable to use steel of known origin?

Most knives are made up of several parts. These may be structural, aesthetic or mechanical. In this last category, we find the blade: for it to be effective and durable, it must meet a number of criteria. In particular, it needs to be hard and tough, more or less depending on its function, as it must not be damaged, cracked or disaffected too quickly if it comes into contact with another hard material (a fork, hard wood, a stone). This is why hardening steel is used: by applying a suitable heat treatment (austenitizing, quenching, tempering), its crystalline structure can be changed and its efficiency significantly enhanced.

A number of problems can arise when hardening steel of uncertain quality, such as scrap steel.

- the steel is hardenable, but we don’t know its austenitization temperature (the temperature to which the steel must be heated before being cooled). Hardening doesn’t work and the steel is too soft: it won’t cut much, and not for long.

- the steel is non-tempering, and will not harden the blade. Please note: there are experts in knife making from recycled steel, and it’s an exciting and remarkable craft. But in all cases, they are experienced professionals.

Where to buy steel?

N.B. : i’m french, so it could be unrelevant for you!

When it comes to finding consistent-quality steel in small quantities in France, there are few options, especially if you want to keep shipping costs to a minimum. Serious suppliers include

- Eurotechni, which has an extensive catalog of steels, other metals and knife making accessories.

- Mercorne, specialized in knife making materials.

A final word of advice: beware of well-referenced online stores with oddly worded tutorials and curiously inexpensive materials. Sounds too good to be true? It is ;)